Why do not all firms engage in tax avoidance?

Higher after-tax cash flows and firm value: the benefits of legal tax-avoidance. Engaging in tax-planning activities that aim to avoid taxes legally thus seems to be a reasonable strategy for every firm. However, empirical studies show that not all firms engage equally in tax avoidance. While the current literature has a difficult time explaining the wide variation in tax avoidance across firms, Martin Jacob and Anna Rohlfing-Bastian, together with Kai Sandner, developed a formal model that manages to explain a part of this variation.

Contrary to what is widely assumed, empirical studies show that not all firms engage in tax avoidance, despite the fact that the monetary benefits of legal tax planning activities cannot be denied. Some firms even pay tax rates above the statutory tax rate. So why is it not equally attractive for firms to engage in tax-planning? This is a question many researchers have been interested in. Several empirical studies document the so-called “Under-Sheltering Puzzle” referring to the puzzling observation of not all firms engaging in tax avoidance. However, researchers have a hard time in fully explaining these cross-sectional differences. We designed a model that contributes to explaining this puzzle: It provides a theoretical framework for testing and explaining cross-firm differences in tax planning.

Our model

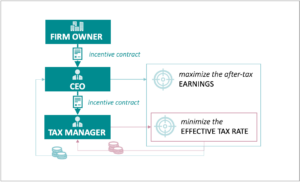

Our model focuses on the strategic interactions between three actors: the firm owner, the CEO, and the tax manager (who is subordinated to the CEO). We assume that the interests of these three might differ from each other. Whereas the firm owners’ interest focuses on the success of his company, the CEO and tax manager are assumed to behave in an opportunistic way that maximizes solely their individual utility. To motivate the CEO and the tax manager to act in the firm owner’s interest – better known as moral hazard – an effective incentive system needs to be established.

Accordingly, in our model the firm owner offers an incentive contract to the CEO, who gets rewarded for his effort to maximize the after-tax earnings. In order to be successful, the CEO must not only ensure that the pre-tax earnings are as high as possible, but also that the effective tax rate (ETR) is correspondingly low. The tax manager is responsible for the latter. For this reason, the CEO in turn offers an incentive contract to the tax manager, who is compensated on the basis of outcome under his control, namely the ETR. Both will earn higher wages if they are successful in their efforts.

Balancing costs and benefits

On the basis of our model, we conclude that a firm’s decision to engage in tax planning rests on the balancing of expected benefits and costs associated with these activities. In particular, the decision to engage in tax planning depends on interaction between the following factors: 1) the amount of monetary incentives, which need to be payed to motivate CEO and tax manager to exert high effort on revenue generation and tax planning (incentivization costs) 2) the potential to increase earnings and 3) the firm-level costs, such as facing a large reputational damage (reputational costs) or being under constant surveillance by government agencies (political costs).

To illustrate our model outcome, we applied the model to two specific cases. We compared public with private firms and family with non-family firms.

Public vs. Private Firms

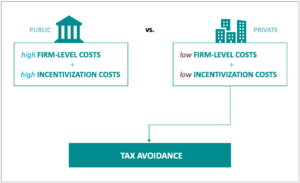

Who is more prone to aggressive tax planning? Private or public firms? What would you expect? Based on our model, the answer is quite clear: Due to several factors private firms are usually more likely to engage in tax avoidance.

For example, their lower exposure to the public plays an important role. Public companies are much more in the public eye than private ones, they have to disclose a significant amount of information. As such, their tax planning activities do not go by unnoticed. Too aggressive tax planning could therefore easily damage the firm’s reputation among stakeholders and the public. The relationship between the firm and the tax authorities could also suffer, which may limit the possibilities for tax avoidance in the future. Accordingly, aggressive tax planning is less attractive for public firms due to higher reputational and political costs.

And there are even more reasons: In the case of private firms, ownership tends to be more concentrated. This means that these owners with larger shareholdings have stronger incentives to monitor management closely, since their personal success is strongly linked to the success of the business. Furthermore, there is a greater overlap of ownership and management within private firms, which means less delegation. In both cases, the owner needs to set less financial incentives to encourage the CEO to increase the tax manager’s motivation to engage in tax planning.

Family vs. Non-Family Firms

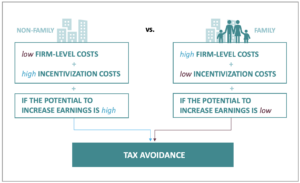

Our comparison of family and non-family firms paints a slightly different picture. The results are somewhat ambiguous. Nevertheless, one thing is quite clear: within family firms, a negative corporate reputation is closely linked to a negative personal reputation, since the persons in charge regularly have closer ties to each other and the firm. This is why family firms tend to avoid actions that could damage their reputation, such as aggressive tax planning. Are family firms thus generally less prone to avoid tax than non-family firms?

Our model reveals: it depends, because there is a crucial counterweight to those high reputational costs: the higher concentration of ownership and the significant overlap of ownership and management within family firms. Therefore, family firms usually have to spend less incentivization costs, which in turn increases their likelihood to engage in tax planning.

To a certain extent, both aspects balance out. The potential to increase earnings becomes a pointer on the scale. It decides whether the scale will move to one side or the other. If the potential is low, family firms are more likely to engage in tax avoidance. Lower incentivization costs seem to be the driving factor for this decision. They make aggressive tax planning less costly and therefore more attractive to family firms. When the potential to increase earnings is high, the threat of reputational damage can outweigh the advantage of lower incentivization costs. In this case, family firms are less likely to engage in tax planning than in the case of low potential to increase earnings.

Impact

Our results are important for the society to understand that not all firms are equally prone to avoid taxes and why not all firms avoid taxes. Since corporate tax avoidance is an issue on top of the agenda of policy makers, for example, the OECD and the G20, it is important for the society to understand which firms are affected more by changes in regulation (those that are more likely to avoid taxes) and which firms are less affected by anti-tax avoidance regulation (those who avoid less taxes to begin with). We look forward to future work taking to our model predictions to the data to assess its empirical validity.

To cite this blog:

Jacob, M., & Rohlfing-Bastian, A. (2020, February 11). Why do not all firms engage in tax avoidance?, TRR 266 Accounting for Transparency Blog. https://www.accounting-for-transparency.de/why-do-not-all-firms-engage-in-tax-avoidance/

More Information

In the principal-agent theory, moral hazard describes the possibility of an agent who is acting on behalf of the principal to exploit his information advantage in his own favor and thus to the disadvantage of the principal. Through profit sharing acting against the interest of the contractual partner becomes unattractive.

In our paper, we build on the idea that the tax-planning decision is influenced by moral hazard. To prove that, we developed a principal-agent-model with one principal (firm owner) and two agents (CEO and tax manager). We decided to use a standard hidden-action model with limited liability, to which we introduce hierarchical contracting responsibilities.

In order to account for the various ways how firms engage in tax planning and the generation of earnings, our model allows for varying sequences of these activities. In particular, our model can be applied to simultaneous decisions (Model: S) and sequential decisions where tax-planning succeeds the generation of earnings (Model: ET). In reality, it is not clear whether the sequence is a choice variable or not. For these reasons, we keep the model as flexible as possible.

Related Content

Fact or fake news: Do German corporations pay only two thirds of the regular tax rate?

Huber and Maiterth scrutinized Jansky’s study, and conclude that the difference between the regular tax rate and effective tax rate is, in fact, negligible.

Read more

Responses