Transparent Research

The first ideas for a Collaborative Research Center on the topic of transparency within taxation and accounting emerged during a bilateral meeting between Caren Sureth-Sloane and Joachim Gassen early 2017. From there on things moved fast; a group consisting of engaged researchers was quickly formed, initial meetings were being held, and preliminary proposals were written. In this first post the initiators and spokespersons of the TRR 266, Caren Sureth-Sloane and Joachim Gassen, look back at how the project came to life, and explain why transparency is not only the subject of their research but also central to their work philosophy by means of FAIR data and open communication. In subsequent blog posts the members of the TRR 266 will share their research and write about their questions and findings in relation to current topics, developments and events.

How did the topic of transparency in accounting and taxation emerge during that brainstorm early 2016?

We met to discuss possibilities for future collaborations, and when discussing themes and possibilities it soon became clear that with “accounting for transparency” we were on to something that offered us to do fundamental research as well as develop an impact on society and the economy. These were two criteria that were very important to us. The latest financial crises and public outrage about multinationals not paying their fair share of taxes have fueled public demand for transparency. For example, prominent accounting fraud scandals and excessive shifting of taxable profits by global corporations have led to concerted regulatory actions with the aim of increasing firm transparency. Consequently, both the amount of available information as well as the regulatory burden of firms have increased substantially world-wide. However, whether this increased level of both information and regulation actually has generated more transparency and its expected positive societal outcomes, is unclear.

We discussed how economic research on regulation has made significant progress in the last decades by focusing on general mechanisms and by testing generalizable models of regulatory effects. However, we thought that moving towards more detailed institutional analysis, focusing on specific regulatory regimes would be promising and allow us to exploit both the technical and institutional expertise in a tentative research team of accounting and tax researchers. The main advantage of this increased focus on detail is that the resulting empirical findings from the field have a higher level of internal validity because the underlying models fit the institutional infrastructure. Even though this strong focus on details means that the findings cannot easily be extended to related problems or situations, the high level of internal validity means that “knowledge that matters” is created.

The focus on accounting, taxation and transparency is clear. But how exactly is transparency defined within the project?

We understand transparency as the quality of information generated, distributed, received, and processed by economic agents. In this regard, quality is a multi-dimensional construct comprising disclosure, accuracy, and clarity of information. Accounting affects transparency whenever it affects the quality of information as distributed to and processed by internal or external stakeholders. Consistent with a sender-receiver framework of information exchange, the sending agent (regulator, managers in firms etc.) can influence the quality of accounting information, for example, by incorporating more details, disclosing it to a broader audience, by auditing it to enhance its accuracy, or by standardizing recurrent information to improve its clarity. Private information gathering and processing activities by other economic agents (e.g., stakeholders, social media) also affect the quality of information.

The two main questions to be answered by the research group are “How does accounting affect transparency?” and “What are the effects of transparency?”. Why is a Collaborative Research Center encompassing 23 projects necessary to answer these two questions?

As we have outlined above, in contrast to traditional research programs in economics that use relatively abstract models, our research program will study a wide set of institutional designs in detail. This means that we will address problems of organizational information flows where decision makers such as managers, investors, and other stakeholders including regulators and tax authorities are involved. This focus on field data, meaning on observations of real life phenomena, enables us to study regulatory effects in the setting where they occur. While investigating human behavior in the laboratory allows for tight controls and thus high levels of internal validity, the regulatory questions that we are interested in cannot easily be transferred to the lab. Managers behave differently from students. Professional investors do not act like retail investors. Taxation systems are too complex for a 15-minute lab briefing. To achieve a balance between internal and external validity we will develop specialized models incorporating the complexity of our regulatory settings and test these models on observational data using field experiments or quasi-experimental settings optimized for causal inference. In order to address our general research questions, we need a wide array of projects covering diverse settings to explore a wide set of institutional designs in detail. Also, we will pool the expertise from managerial and financial accounting as well as taxation to bridge the interdependencies of these fields. In combination, we hope that our 23 projects will help us to better understand how accounting affects transparency and how transparency affects society. Thereby we will contribute to both academic debate and pressing real-life issues such as the development of future tax systems, questions of capital market regulation and the design of incentives schemes or financial reporting regimes.

More Information

There is no formal definition of Open Science, in fact it is an umbrella term covering various movements fostering sharing and collaborating. The European Commission describes Open Science as representing a new approach to the scientific process based on cooperative work and new ways of diffusing knowledge by using digital technologies and new collaborative tools (European Commission, 2016). The OECD defines Open Science as: “to make the primary outputs of publicly funded research results – publications and the research data – publicly accessible in digital format with no or minimal restriction as a means for accelerating research; these efforts are in the interest of enhancing transparency and collaboration, and fostering innovation” (OECD, 2015:7). As such, Open Science encompasses aspects such as open access, open data, open source software and citizen science. It is important to note that Open Science concerns the entire research cycle; researchers should share and collaborate as early as possible in order to entail a systematic change to the way science and research is done.

Related posts

Open Science in corona times

In response to the COVID-19 pandemic three new projects have been initiated by the Open Science Data Center of the TRR 266.

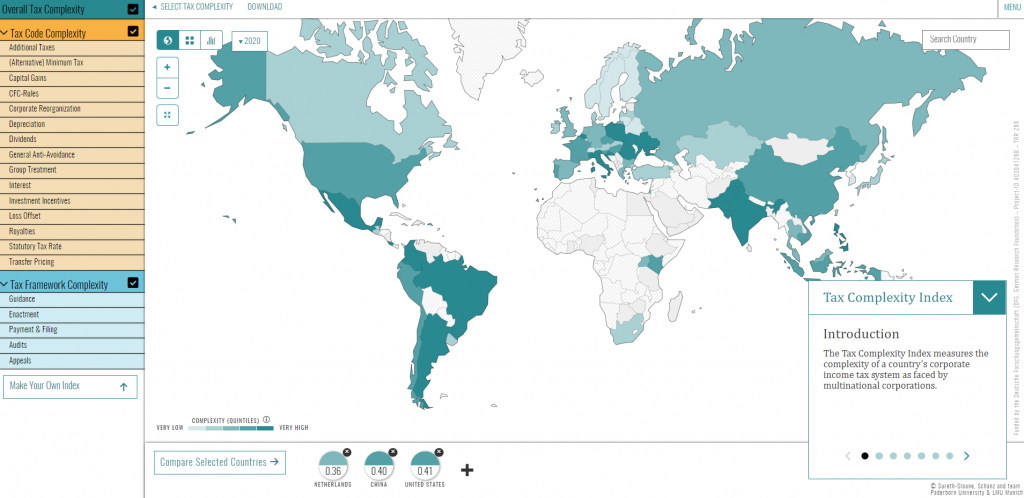

Read moreThe Tax Complexity Index – An innovative measure to analyze tax complexity across countries

Recently, the relevance of tax complexity has increased significantly. This is a potential threat for the economy and society since the negative consequences of complex tax systems can jeopardize economic prosperity and encourage undesired tax planning as well as tax avoidance.

Read more

Responses